Priority Two: The key to unlocking The UK Rare Diseases Framework

Written by Dr Lucy McKay, CEO of Medics4RareDiseases

The new UK Rare Diseases Framework has identified four key priority areas for addressing the challenges faced by those living with a rare disease. However one Priority in particular is the key for unlocking the other three: “Raising awareness of rare diseases among healthcare professionals”. This is going to be the hardest obstacle to conquer but it will allow for the other three priorities to truly come into their own. Here I present how we can start to activate the key to the Framework – Priority 2 .

Medics4RareDiseases is a charity that is driving an attitude change towards rare diseases amongst medical students and doctors in training in order to reduce the diagnostic odyssey and improve the patient journey. Members of the M4RD team have been striving to raise awareness of rare disease for 10 years now, ever since we started a medical student society at Barts and The London. Therefore we wholeheartedly agree that systemic change is needed within healthcare if we’re going to achieve the best outcomes for those living with a rare disease. It also means that we have experience in making this happen.

Here I will lay out how I think we need to approach “awareness”, in order to unlock the potential of The Framework, as the CEO of M4RD, a rare disease family member and as a qualified doctor.

You cannot expect change to be implemented when those you want to implement it are unaware of the problem you’re trying to solve.

Dr Lucy McKay

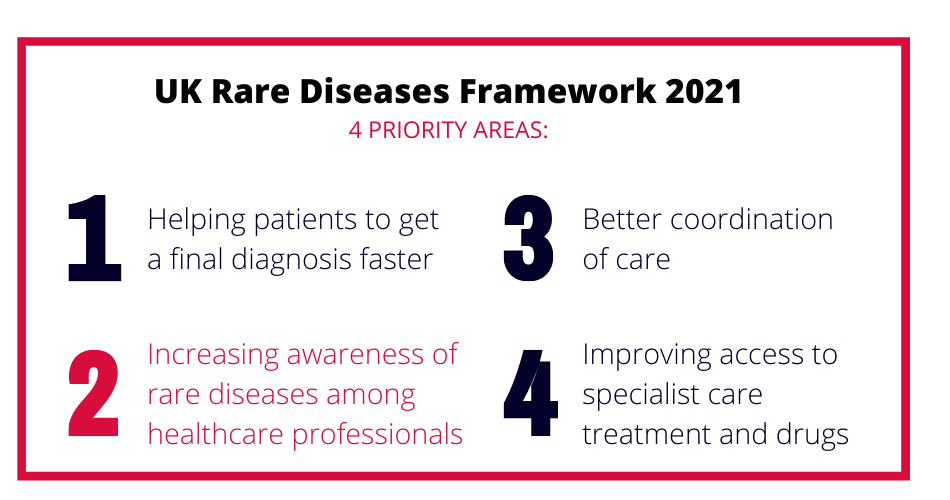

The UK Rare Diseases Framework 2021

On 9th January 2021 the greatly anticipated UK Rare Diseases Framework was published by The Department of Health and Social Care (DoHSC). This important update to the original 2013 UK Strategy outlines key priorities that need real action in order to improve the lives of those living with rare diseases, as well as supporting the personal and professional communities around them.

Representing M4RD I took part in the Big Conversation announced by Baroness Nicola Blackwood in July 2019 that resulted in the creation of this new Framework. My message to the team at the DoHSC was that medical education in the basics of rare disease is essential to build on the commitments made back in 2013. You cannot expect change to be implemented when those you want to implement it are not aware of the problem you’re trying to solve. Early and consistent medical education about rare disease will prepare the medical workforce to work alongside other stakeholders to achieve any future goals. I also advocate the retiring of the meaningless and powerfully obstructive phrase “common things are common” from medicine.

The Framework published this month represents Phase One and it focuses on four key Priorities. It “sets out a high-level vision for each of these priority areas, shared by all UK nations, providing a strategic direction for the UK’s work on rare diseases across the next 5 years, at which point it will be reviewed.” During Phase Two each nation will decide on an action plan that they will implement in order to achieve this vision. This is where the real change can be implemented. The M4RD team plans to put all the knowledge and experience we’ve gained over the last 10 years to help inform Phase Two.

The Framework is a testament to the progress M4RD has made so far

The four key priority areas will not be surprising to anybody who has attended an M4RD event – which is reassuring in consistency but shows that progress is still slow.

Priority 2 is the raison d’etre of Medics4RareDiseases and so it is exciting to see it clearly identified within the Framework by DoHSC. M4RD understands that it is unfeasible for any medical professional to know about over 7000 rare diseases therefore we need to take a non-disease specific approach to medical education, foregrounding what it’s like to live with a rare disease and how medics can help ease the suffering of patients. I was glad to see the new Framework make reference to this way of thinking which demonstrates that the rare disease community are taking a more strategic approach to this issue rather than each individually competing for time on medical curricula. M4RD focuses on medical professionals in particular because they are key to diagnosis, care coordination and treatment. We ask them to #daretothinkrare and focus on the common challenges faced by people with different diseases.

The inclusion of this statement in The Framework demonstrates progress and is also exciting for me personally, as prior to being CEO of Medics4RareDiseases I was a practising NHS doctor. When I first started speaking publicly on the issue, this was a new concept and even at rare disease events I could receive resistance to it. However this model of thinking is not new in medicine or healthcare. We have other patient models or scenarios that are not united by an underlying condition but rather similar needs, risks and impact that patients share. For example every medical student is able to start a management plan for an admission of an immunocompromised patient, whether this is due to systemic disease, infection or an iatrogenic cause.

We must strive for a medical profession that can similarly hear “rare disease patient” and think of: multi-system disease, a coordinated care approach, research opportunities and psychological support for example. This is an achievable goal and M4RD is already putting in a lot of the groundwork in to make it happen with events, medical student engagement and soon, Rare Disease 101, our new online medical education module.

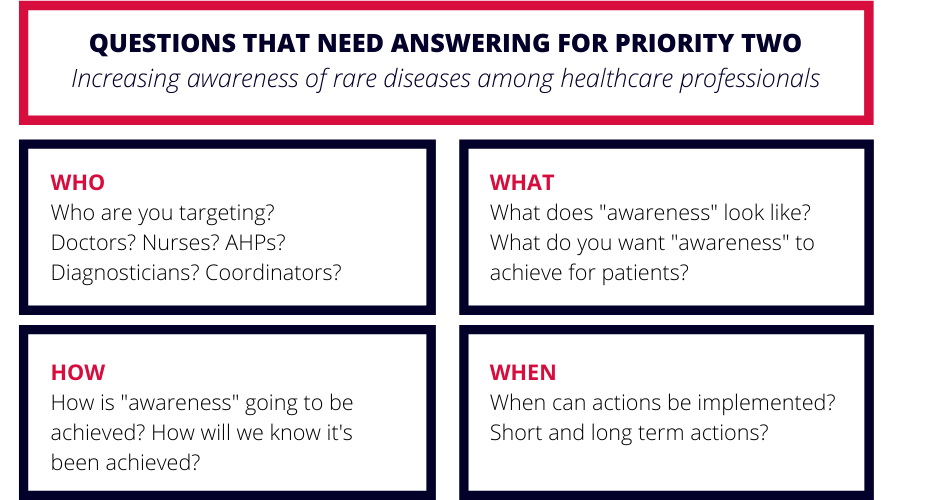

This leads to some key questions that must be defined and answered before the work progresses to Phase Two which I will lay out below.

WHO do we mean when we talk about “Healthcare Professionals”?

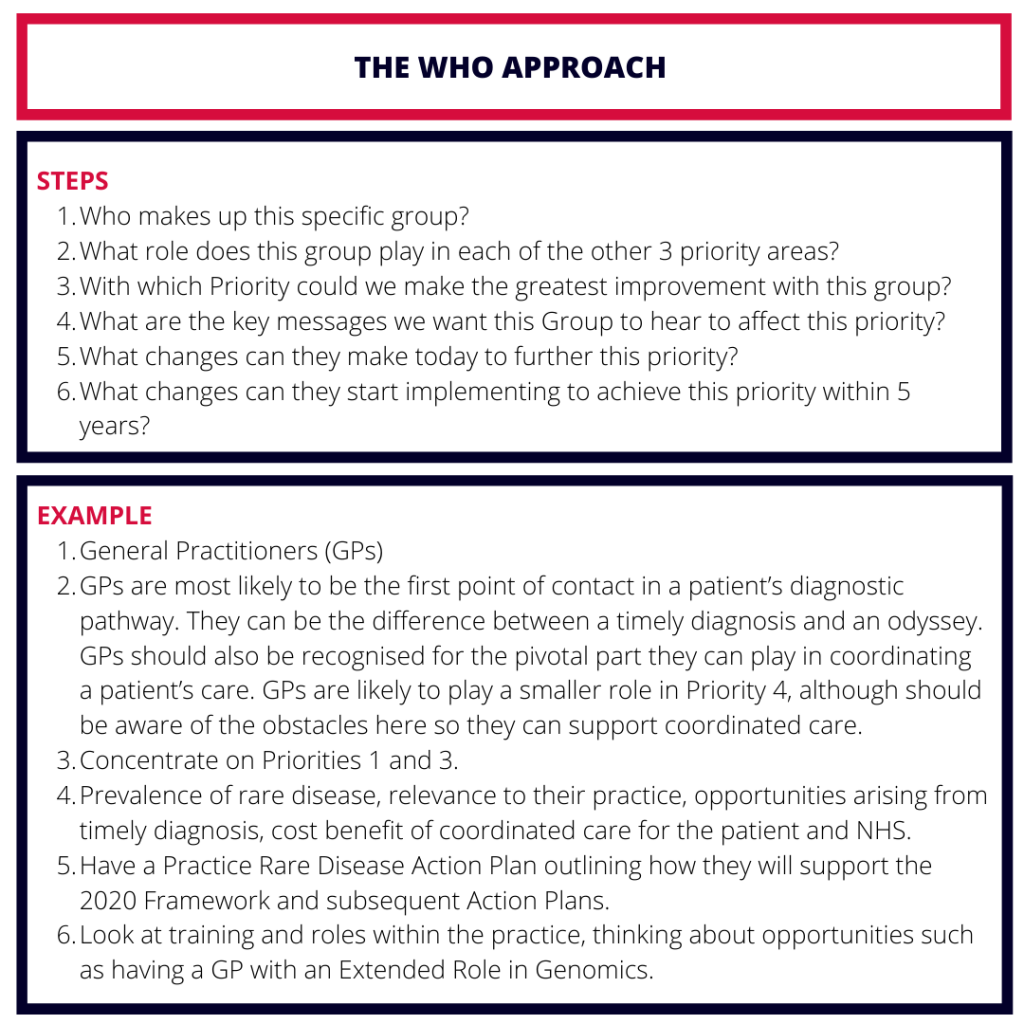

Priority 2 is a lofty goal but it is achievable. The term “Healthcare Professionals” encompasses a huge group of people consisting of nurses, paramedics, midwives and doctors and 14 allied healthcare professions (AHPs). As we decide the actions on the Action Plans we must define the WHO for each element.

Each of these professions will have a unique insight into a patient’s experience and will play their own role in that patient’s journey. Even within one profession, Medicine, a doctor’s skills and experience can vary wildly depending on their training level, the placements they’ve had, the hospitals they have worked in and the specialism they are pursuing. Therefore this one heterogenous group described as “Healthcare Professionals” needs breaking down in order to create specific actions that are achievable for each individual.

WHAT do we specifically want from Healthcare Professionals?

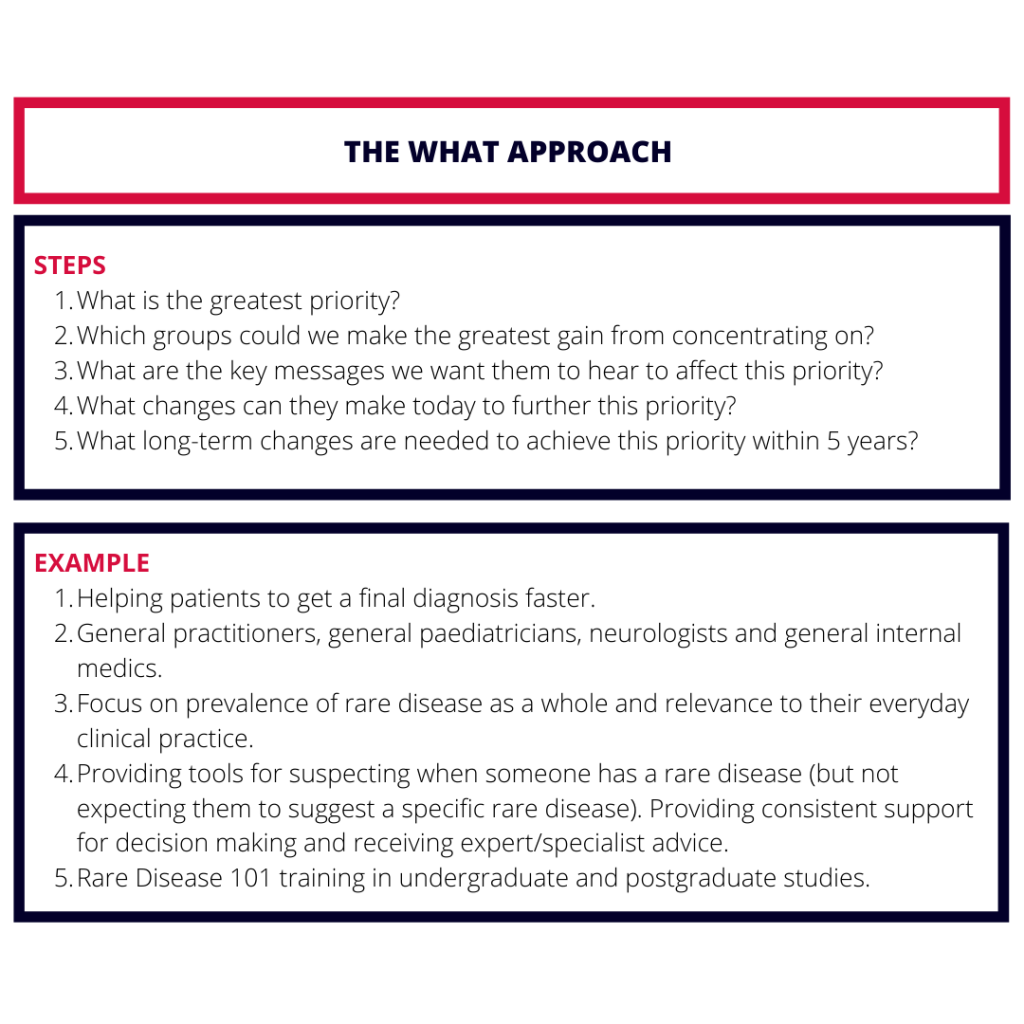

The approach needed for increasing awareness of rare diseases among healthcare professionals is also going to depend on WHAT we are specifically trying to achieve with this “awareness”? This is where the other three priorities come into play: 1. Helping patients get a final diagnosis faster 3. Better coordinated care and 4. Improving access to specialist care, treatment and drugs.

We will need to target different professions and different groups within those professions in order to achieve the change needed for each of the other three priorities. A GP is going to need a different focus than a Clinical Geneticist when it comes to diagnosis. A surgical ward nurse is likely to need a different approach to a specialist nurse in a Tertiary Centre in order to better coordinate care.

HOW can we approach Priority 2?

Priority 2 is not a small one and I believe it needs a strategy of its own. I suggest a two-armed approach. Arm 1 is a Healthcare Professional (HCP) -Led Approach (The WHO Approach). Arm 2 is a Priority-Led Approach (The WHAT Approach).

We need patients and healthcare professionals both sharing experiences to unravel this issue

We need patients and healthcare professionals to share their experiences in order to understand the obstacles standing in the way of each of the 4 priorities. 68% of the responses to the Government survey were from patients which reassures me that the priorities chosen therefore reflect true unmet need. However only 7% were from Healthcare Professionals so now we need to hear from those in the healthcare workforce to understand why this is.

It is imperative that those involved in creating the Action Plans consult the frontline professionals that they are targeting, after all, they will be pivotal to implementing these plans. If we want to make a real difference in this area we need to be bringing healthcare professionals into the conversation from the very beginning.

Medical Education, Medical Education, Medical Education

We need to now look to the group of people that are essential to three of the Framework’s four Priorities and the focus of the remaining priority – Healthcare Professionals. We know about the unmet needs of patients and now we need to equip those who can fulfil the needs to do so. This process starts with consulting healthcare professionals about why they believe these unmet needs still exist despite the efforts following the UK Rare Disease Strategy in 2013. My suspicion is it will be due to a basic lack of understanding of the relevance of rare disease to everyday clinical practice.

This is why I believe that everything we do in rare disease needs to be complemented by medical education in order to systematically improve the patient experience and reduce the diagnostic odyssey.

L to R: Dan Jeffries, Dr Debra Fine, Dr Lucy McKay, Jo McPherson and Dr Hannah Grant

15th February 2021 @ 3:35 am

Fantastic perspective, expertise and clear actions for a rather complex and still resistant idea (In New Zealand). Thank you so much for the work, advocacy and persistance provided to this vital area of awareness of rare diseases.

We hope to follow in your rather large footprints and gain a National Framework in New Zealand eventually!!

Please sign and share our petition if this resonates with you;

https://our.actionstation.org.nz/petitions/reform-our-health-system-to-include-all-new-zealanders-living-with-a-rare-disorder?

22nd April 2021 @ 8:28 pm

Thank you Lisa! We’ve signed. And if there is anything we can do to adapt our materials for your audience please do let me know. Best wishes, Lucy

27th February 2021 @ 10:13 am

Hello! I am a qualified doctor (MRCP 1996) but am no longer working. I have recently been diagnosed with a very rare disease (EGPA) -think miniature pink zebra- after years of seeing specialists. Despite my medical background and being able to self-advocate and navigate the system, and that I had essentially diagnosed myself, I had a hard time getting taken seriously (‘anxious medic’). In fact I had to become seriously unwell before getting finally diagnosed.

The experience made me think about the difficulties of diagnosing rare disease.

I had an idea which may be of interest regarding medical education and came across your excellent piece above.

I feel that there is little feedback in the learning cycle of physicians and so they do not realise when they ‘miss’ cases which later turn out to be rare diseases. Of course many diseases are not diagnosable in their early stages as they are are often an incomplete constellation of signs or symptoms so they are not truly ‘missed’. And even for diseases when the elements are all present it is understandable that doctors cannot be trained in all rare diseases. So a doctor who has ‘reassured’ a zebra that they have ruled out all the usual suspects will not find out that the patient was subsequently diagnosed with a rare disease when more obvious, or typical stripes emerged. They get the impression that they are doing a good job and presume that the discharged patient has gone away reassured that there is nothing serious wrong.

This is particularly the case when the patient has gone to a series of specialists often in different hospitals in search of answers. The doctor will then have a false idea of the prevalence of rare disease as a whole, as there is no feedback in the system. GPs do get feedback as they are the central point of contact, but as generalists it is a big ask for them to make rare diagnoses.

My suggestion is that when a very rare diagnosis is made and coded, an alert should be sent automatically to the specialists who have seen that patient to notify them of the outcome. This would be a point of interest or learning rather than any judgement on whether a diagnosis could or should have been made earlier. This would serve as a reminder to physicians that zebras are more common than we think and are often missed.

This might help the mindset to change, and even help with pattern recognition in diagnosis.

I think it should become as acceptable for doctors to present a rare case they missed at a meeting as one they diagnosed.

If there was a worry that some doctors would this feedback difficult they could opt out or in to these notifications. I would envisage it to be similar to the Yellow card side-effect system but maybe a black and white striped virtual card instead!

22nd April 2021 @ 8:27 pm

Hi Paula, thank you so much for your insights and I think this is something I have not thought about enough so I am really grateful for you taking the time to describe the problem to me. You’re absolutely right that the lack of feedback perpetuates the perceived rarity of rare disease. This would be a really interesting subject to discuss more. If you would like to please email me on lucy@m4rd.org